My Coma Diary

Uncover the Truth from Trauma: From the Moments of losing my Conscience, the Frozen Time Within the Coma, the Waking up, the Recovery and Everything That Makes me up till Today

Twenty-five years ago, a single moment shattered my world. At fifteen, I was just a kid, navigating the familiar rhythms of school and home. Then, a bicycle ride, a busy intersection, and a sudden impact changed everything. This is the detailed story of my coma, pieced together from the diaries that my family kept during those agonizing days, interwoven with my own fragmented memories and the echoes of those stories.

It's a story of fear, hope, and the enduring power of love. It's a story of survival from where I was to where I am today. From falling down, to stepping up. From fully disabled to atheltic performance. From setbacks to resilience.

My life without TBI

As a teenager, life up until the day of my coma felt much like many others will remember from their own youth. I was busy exploring—making friends, discovering love, and diving into all the possibilities ahead. I carried the energy and excitement of what felt like a great beginning to my life.

I grew up in a loving family, though like any normal teenager, I had my share of struggles. Real experiences began to shape me, especially as my first ambitions of becoming a professional soccer player started to take form. I wasn’t a kid who went looking for trouble. I stayed away from drugs, though by then I had already tasted my first beers.

Dead or Alive? Day 1

The Day of the Car Accident

I remember nothing of this day or of the two weeks leading up to it. Everything I know about what happened comes from witness accounts and my family’s memories.

It began like any ordinary morning. I was 15, waking up, eating breakfast, and grabbing my school bag. Living in a rural area, my bike was my main way to get to school. At about 7:30 a.m., I set out on the familiar four-mile ride, planning to arrive by 8:00. The route mixed quiet country roads with the edges of the small, orderly city where my school sat. Mornings like these are etched in my memory - the crisp air, the slight chill that made me pedal faster, the anticipation of seeing my friends. I had no way of knowing this seemingly normal morning would change my life forever.

Around 7:55 a.m., I reached a busy intersection. A truck was oddly parked just before the crossing. As I cycled around it, I unknowingly moved into the path of an oncoming car. The collision catapulted me across the road, and I landed on the left side of my head. The trauma from that impact still affects the right side of my body today. I was unconscious, unresponsive. Someone called for an ambulance.

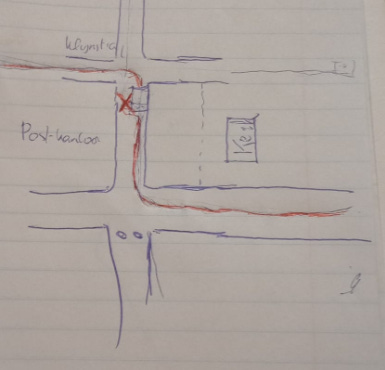

Paramedics arrived quickly and gave me first aid at the scene. In my family’s diary, I later found a sketch of that day: the red line showing the road I usually took to school, and the red X marking the exact spot where the car hit me.

News of the accident didn’t reach my family right away. This was before mobile phones were common. Word spread first at school - some students, including my niece Miranda, saw the aftermath. The principal, hearing whispers in the corridors, phoned my parents with what little he knew. My mother frantically called the police and local hospitals, desperate for information, but no one could tell her anything. Finally, she learned I had been airlifted by a trauma helicopter to a university hospital.

But the truth was different. While the helicopter had arrived to provide emergency care, doctors decided that flying would put dangerous pressure on my already injured brain. Instead, I was rushed by ambulance to the hospital.

When my family arrived, they found me lying still in a hospital bed. To them, I looked peaceful - no obvious sign of the violent accident I had just survived. My sister Jolanda later told me how surreal it felt: “One minute you’re riding your bike to school, the next you’re in intensive care, surrounded by tubes and machines.” My mom said, machinery and tubes aside it looked like I was only sleeping - a cruel illusion.

The neurologist explained I had suffered brain damage. There was bleeding at the front and back of my brain - tiny but dangerous, causing swelling that could shut down vital functions. The next three days would be critical for survival, he warned.

No one knew if I would survive. My sister Nicole, overwhelmed with guilt, wrote: “Will you ever leave the hospital alive? I don’t want to lose you. I see now what a wonderful brother you are, and I feel guilty for not seeing it before. I want to start over and take you on trips, to truly enjoy life. Why did this happen?”

That night, my sisters went home while my parents stayed at the hospital, keeping vigil. Eventually, a nurse convinced them to get some rest in a spare bed nearby. There was nothing left to do but wait - and hope my body and brain would heal from this experience. As I lay in a deep coma, no one else slept that night.

Dead or Alive? Day 2

Fear of the Uncertain

The second day of my coma was a whirlwind of emotions for everyone around me. My sudden, inexplicable absence from life left my family, friends, and classmates reeling in shock and worry. The mystery surrounding my condition only amplified their anxiety. For my immediate family, this marked the beginning of a daily coming and going to and from the hospital, accompanied by a tremendous amount of worry, sadness and insecurity. A constant cycle of hope and fear as they sought any sign of progress.

The morning brought a nerve-wracking wait for the results of my CT scan. At 11 am, the news finally arrived. The images of my brain offered a glimmer of hope – the results were promising. Doctors decided to stop the sleep medication, a positive step that meant I may wake up naturally, on my own time, when I was naturally ready for it? But was I really? Nobody knew.

Later that afternoon, around 3:30 pm, another significant milestone: the ventilator was removed. I was breathing on my own. However, I still had numerous tubes in place, managing oxygen levels, nutrition, and other vital functions. These tubes, though necessary, were a source of irritation, causing me discomfort that my family could see. They described moments of deep sleep alternated with periods of restlessness, where I would move aggressively, seemingly agitated by the tubes.

My lungs were congested with mucus, making breathing difficult. Some of the tubes were actually suctioning out the mucus to help me breathe easier. Unfortunately, the irritation from the tubes became so intense that I started to fight them, becoming sometimes extremely aggressive in my attempts to remove them. This led the doctors to make the decision to restart the sleep medication. I was not ready for waking up.

Sedative medications in comateus patients are used only if medically necessary - either to induce/prolong coma for protection or to manage agitation and procedures, which was the case in my situation.

Throughout this ordeal, my family maintained a constant presence at my bedside. My parents and two sisters took turns staying with me around the clock. Their days were a rollercoaster of emotions. Tears of sorrow and fear, the agonizing "why me?" and the uncertainty of my survival, were interwoven with tears of relief that I was still alive. Every sliver of positive news from the neurologist, no matter how small, was met with an outpouring of joy.

While my family was intimately involved in my care, my friends, classmates, and teammates felt a different kind of helplessness. They were on the sidelines, desperate for information and updates. My sisters became the vital link, regularly contacting my inner circle, school, and other friends to keep them informed about my condition. They tried to bridge the gap between the hospital room and the outside world, sharing any news, however small, with those who cared so deeply.

The reality of my absence hit home for my sister Jolanda on the second day. She walked into my sleeping room at our parents house. It was as if she was ‘‘stepping into a dream that didnt feel real and where the main character was going through a nightmare’’. The room, a snapshot of my life before the coma, felt empty but appeared as if I just was stepping out of it. Posters of my favorite artists and sports teams adorned the walls, and my belongings were scattered about as if I was coming back soon. The room, so full of my presence just a day before, now echoed with my absence, a stark reminder of the fight I was facing.

Dead or alive?: Day 3.

Little Signs of Improvement?

Jolanda's diary opens on the third day of my coma, her words raw with the disorientation of our new reality: "It's only the third day, but it feels like weeks." seeing me with normal clothes on in the hospital bed. .

The world as my family knew it had dissolved, replaced by the sterile, fluorescent-lit reality of a hospital room. Their days became a relentless cycle of visiting me, their son, their brother, lying motionless in a coma.

Days were haunted by sleepless nights, mornings by phone calls to family, friends, and my school. Each conversation a desperate plea for normalcy in a world that had irrevocably shifted. Emotionally, they were on a rollercoaster, their hopes rising and plummeting with every whispered update from the medical staff, every flicker of perceived change in my condition. Each piece of news, however small, became a life raft in the turbulent sea of their anxiety.

In the morning they saw me lying on my left side – a surprising discovery, suggesting I had used my right side, a cause for jubilant celebration. But their joy was quickly tempered by a new, gnawing fear. My right side, the one I had instinctively used, remained largely unresponsive, a chilling reminder of the long and arduous road ahead.

On that third agonizing day, the large tube regulating my oxygen was removed, a moment pregnant with both hope and trepidation. A nurse suggested I might be moved from the intensive care unit to a neurological unit, a glimmer of progress in the darkness.

This fragile hope hinged on my ability to cough up mucus on my own, a simple bodily function that suddenly held the weight of my future. By day's end, the decision was made: I remained in intensive care. Pneumonia, a cruel and relentless adversary, had taken root in my vulnerable lungs, demanding constant suctioning and increased oxygen.

My family, their eyes perpetually searching for any sign, any flicker of recognition, noticed a subtle shift. I was moving more actively, a tiny spark in the vast emptiness of my unconsciousness.

Then, a breakthrough. My eyelids fluttered open. A chink of light pierced the darkness. Was it mere reflex, or something more? Did I see them? Did I hear their desperate whispers? Was this the beginning of my return, or just a fleeting illusion in the surreal landscape of a coma? The question hung in the air, heavy with anticipation, a silent plea for a miracle.

The Journey Towards Healing: Day 4 - 7.

Navigating the Intensive Care Journey

I am in the intensive care unit, surrounded by the sound of machines around me and the care of dedicated hospital staff. My family has created a rotating schedule to be by my side as much as possible - my sisters come during the day, and my parents take the night shift, staying until around 10 PM.

After they leave, I spend the midnight hours alone. It’s a lot for everyone to handle, but this way, we’re all able to keep going. The hospital staff has been clear: having too many people at my bedside at once isn’t helpful, so this system works best for now.

When my sisters arrive in during mornings, they often hear music playing softly from the radio near my bed. Music has been shown to be a powerful tool for healing, especially for people with severe brain injuries or those in a coma. It’s a small but meaningful part of my recovery journey.

To anyone looking in, I might seem peaceful lying there, but the reality is more intense. The nurse shared with my sisters that I had to be suctioned four times the night before to clear mucus from my airways. This process is very painful, and even though I’m in a deep coma, my body reacts strongly - I pull my legs up to my chest, as if trying to protect myself from the discomfort. Afterward, I’m completely drained, barely moving at all.

Each day, my sisters get an update from the nurses about how I spent the night. They then call my parents, who are at home, to share the news. The same happens when my parents arrive at night - they get an update and call my sisters to keep everyone in the loop. A routine build up by sadness but one that everyone involved takes to keep on going. It’s a cycle of love and communication, even though it’s exhausting for everyone.

At home, my parents and sisters is desperate for rest, but it’s hard to come by. The phone rings constantly - extended family, friends, and loved ones all want to know how I’m doing. While it’s tiring, these calls also bring a strange kind of energy. They remind my family that we’re not alone in this fight, and that support means everything.

On the fifth night of my coma, something small but significant happened: I didn’t need to be suctioned. For the first time, I had a peaceful night without the exhaustion that usually follows the procedure.

My family noticed that my eyes were opening more often and wider than before - a tiny but hopeful sign that my body might be slowly working toward waking up. Still, my sister shared her mixed feelings: “I still hope you’ll wake up any moment, but I’m starting to realize this could take a long time.”

That same day, my football team played their first game without me. They made a video and photo diary of the match, dedicating it to me and my family. My team won 3 against 2. Every time they scored, the goal scorer held up my jersey with my number 6 high in the air. Those images were recorded and sent to the hospital for me, my parents and staff to hear and see, a touching reminder of the love and support surrounding me, even from further away. A soccerfield, me being on it, in what state? Would it ever be possible?

While the accident left little visible damage, most of the trauma was in my brain. The small wounds on my body were healing, but the process was slow because I kept scratching it open unintentionally. The healing of outside wounds at least showed visible signs of improvement, whereas what was happening within my brain remained a mistery.

As we reached the end of the first week, emotions ran high. My family couldn’t help but remember how different life was just six days ago. I was playing football, sharing laughs about things that had no meaning, and dreaming about a future where everything was possible. Now, I’m lying in a hospital bed in coma, fighting for my life in a very uncertain future nobody wants to speak about other than the present.

But on the sixth night, there was a glimmer of hope. The nurse shared that I’d be moved from the ICU to a neurological unit the next day. While this news brought relief, it also came with a wave of anxiety. In my short stay in the hospital, my family has learned that good news on one day can sometimes be followed by challenges the next day. Still, they hold onto hope, knowing that every small step forward is a step toward healing.

Wake up for reality

As hard as it was to face the harsh reality of my condition, life didn’t stop for my parents. They had their own business to run and necessary responsibilities to take care of, even though their hearts and minds were with me in the hospital.

Most days, it felt impossible to focus or be productive, but those small tasks became a kind of remedy - a way to momentarily clear their heads and find a sense of normalcy in the chaos..

During this incredibly tough time, our family, friends, and even far acquitances stepped up in ways we never could have imagined. They surrounded us with support, helping with whatever was urgent or needed. It’s true what they say: “You find out who your real friends are” in moments like these. The love and kindness we received from our community became a lifeline, reminding us that we weren’t alone in this fight.

To anyone out there going through a similar journey - whether you’re the one injured or a loved one standing by - know that healing is a process. It’s filled with ups and downs, but every small victory matters. You’re not alone, and even in the darkest moments, there’s hope. Know that it’s okay to lean on others. Even in the darkest times, there are people who care deeply and want to help. Let them. And if you’re the one supporting a loved one, your kindness matters more than you’ll ever know.

In the most scariest, most disturbing and insecure times it becomes more easy for everybody to find common ground. Help is around everywhere.

The Journey of Mental Healing: Day 8 - 14.

Navigating the Fog of Coma

The first week of my journey was spent in the intensive care unit (ICU), a place where life and death often hang in the balance. On the first day of the second week, I was transferred to the neurological unit of the hospital. This move marked the first real sign of progress, a tentative step toward recovery.

Leaving the nearly dead stage behind, the road ahead remained uncertain - no one could predict what my recovery would look like or where it would ultimately lead to.

My family, grateful for the care I received, bought presents for the ICU staff as a heartfelt thank-you.

While the care I received was rooted in strict, standardized protocols for traumatic injury, the staff’s personalized approach in communicating with my family stood out. Though not traditionally called "first responders", their compassion and dedication to both me and my family were nothing short of extraordinary.

Even in this early stage, my body and mind were in turmoil. I would open my eyes occasionally, but there were no signs of communication or awareness of my surroundings. My bodily functions added to the confusion - I felt uneasy about my stool, unaware that I was wearing a diaper. My family reassured me that it was okay to let go, but the disconnect between my mind and body left me restless. I would sweat profusely, my left hand fidgeting toward my back, unsure of what to do. These small, fragmented moments were glimpses of the internal struggle I faced, even in my comatose state.

The neurologist emphasized the need for "absolute rest," advising that I be shielded from excessive stimuli. He outlined a comprehensive recovery plan that would involve physiotherapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, and even dental hygiene.

A rehabilitation physician was assigned to oversee my progress. The neurologist explained that once I began responding to basic commands, I would be discharged from the hospital to continue my recovery in a specialized rehabilitation center.

Hearing this, my sister was overwhelmed with emotion. She later wrote, “I long for this moment so much that I burst into tears, but I don’t know if it’s out of joy, anger, or fear.” While this news brought hope to my family, I was still far from that stage, remaining in a deep coma.

By April 18, there was another glimmer of real progress - I no longer needed oxygen, and the IV providing antibiotics for pneumonia was likely to be removed the next day. Each reduction in machinery and tubes symbolized a small victory in my recovery.

My family began to notice other signs that I might be "waking up." My eyes stayed open longer, and at times, it seemed I was tracking movement. I began to move my chest more and ramble incoherently, small but meaningful steps forward.

One morning during the second week of my coma, my family was both surprised and alarmed to find that I had pulled out my feeding nasogastric (NG) tube. Despite being restrained for my safety, I had managed to free myself, likely in some way using my right side. A hopeful sign, as that side was paralyzed.

Without restraints, I had a tendency to try to climb out of bed, a behavior that, while dangerous in my unaware state, hinted at a growing physical awareness.

Years later, I would recall a vivid memory of climbing out of bed, sitting in a wheelchair, and even attempting to wheel myself toward the hospital reception. The urge of food was probably my driver to go to the reception. I remember the sun shining brightly, the sky clear and peaceful, and the strange calm I felt as I realized I shouldn’t be there and returned to my bed. Whether this happened or not, during or shortly after my coma, I dont know for sure but the memory remains vivid and comforting that I am near to sure it did happen in one of those moments my family wasnt besides my bed. Therefore no witness accounts to proof it, just memories.

My mother, in her diary, expressed the deep ache of missing our conversations. She wrote, “Will it ever be possible to talk to you again?” Her words captured the heartbreak and uncertainty that come with loving someone in a coma.

More moments of hope. On one occasion, I managed to remove my shirt in bed, leading my family to wonder if I had used my right arm - a sign of increasing awareness. “Are you waking up more?” my sister wrote, her words tinged with cautious optimism.

My sister, in her diary, captured the bittersweet reality of those days: “Just as I want to go home from the hospital, I think to myself: I just wanted to take you home too. You lay there so peacefully, as if nothing had happened.”

On the 11th day of my coma, my parents received a glimmer of hope from the neurologist. He pointed out my small but meaningful reactions - like shifting my body to help a nurse remove my clothes - as signs of progress. Based on these responses, he predicted I might wake up within three days to a week. They were subtle, yet powerful signals that I was fighting my way back into concious existince.

This journey through my trauma and recovery is one of resilience, hope, and the enduring power of love. Recovery is not linear, and every small step forward is a victory. My story is a testament to the strength of the human spirit and the unwavering support of those who stand by survivors, even when the path ahead is uncertain or looking dreadful.

The Journey Towards Waking Up: Day 15 - 21.

Recovery is Never a Straight Line

The third week of my coma marked a shift in the rhythm of life for my family. The initial shock and chaos of the accident had begun to settle into a new, albeit painful, normal.

Each family member was trying to balance their own responsibilities with the overwhelming reality of having a son, a brother, lying in a hospital bed, fighting to wake up.

My oldest sister Nicole, already working, juggled her job with daily visits to the hospital. My youngest sister, in the midst of her school exams, found it nearly impossible to focus on her studies. Her mind was consumed with worry, her heart heavy with the fear of what the future might hold. My parents, running their own business, struggled to maintain some semblance of normalcy, though their thoughts were never far from the hospital room where I lay.

For them, life had become a delicate balancing act—managing their daily obligations while keeping a constant vigil over me. The hospital had become a second home, a place where they spent hours each day, watching, waiting, and hoping for any sign that I was coming back to them.

And slowly, there were signs. My eyes, once vacant and unfocused, began to look more alert. I would sometimes fixate on the people talking to me, as if I were trying to make sense of the world around me. My family clung to these moments, desperate for any indication that I was still there, still fighting.

Yet, despite these glimmers of awareness, I remained unresponsive to specific questions. Occasionally, a word or two would slip out, muffled and incoherent, but enough to send a surge of hope through my family. Was I trying to communicate? Was I on the verge of waking up? No one could say for sure, but the possibility was enough to keep them going.

One of the most poignant moments of the week came when my family returned to the scene of the accident. Standing at the intersection where my life had changed forever, they were confronted with the stark reality of what had happened. The yellow paint on the road, marking the positions of the vehicles involved, brought a flood of emotions.

My parents and sisters couldn’t help but imagine those final seconds—what had I seen? What had I felt? The weight of those unanswerable questions hung heavy in the air, a reminder of how fragile life could be. For my sister Jolanda, the visit was particularly harrowing. She later wrote in her diary, “Seeing those yellow lines on the road, it was like reliving the accident all over again. I kept thinking, ‘What if we had just one more minute? What if we could have stopped it?’ But there’s no going back. All we can do is move forward, one step at a time.”

Back at the hospital, the signs of progress were small but significant. I was beginning to show more awareness of my body, even attempting to comb my hair by myself. My hair, which had been long before the accident, had grown even more during my coma, becoming a tangled mess that my family would gently brush and style for me.

It was a small act of care, but one that brought them a sense of connection to me, a reminder of the person I had been before the accident. Yet, the physical toll of my condition was becoming more apparent. I had developed wounds on my right hip from lying in the same position for so long.

My right side, paralyzed from the impact of the accident, made it impossible for me to turn myself on the other side, and the constant pressure had caused painful sores. The nurses did their best to alleviate the discomfort, but it was a stark reminder of the long road to recovery that lay ahead.

The neurologist remained cautiously optimistic. During one of his visits, he spoke with my parents about the next steps in my recovery. He was particularly concerned about the paralysis on my right side and my ability to speak, but he also talked about the rehabilitation center where I would go once I woke up.

His words were a mix of hope and caution—hope that I would wake up, but caution that the journey to full recovery would be long and arduous. My sister Nicole, listening to the conversation, later wrote in her diary, “I want to believe that you wake up soon, but will that be the same Johan we’ve always known. I’m scared. What if you are not the same? What if you can’t walk or talk? I don’t care. I just want you to wake up!’’

Meanwhile, my youngest sister was struggling to keep up with her normal life. Her exams, which should have been her primary focus, felt trivial in the face of my condition. She tried to study, but her mind kept drifting back to the hospital, to the image of me lying motionless in the bed. When she did manage to go out with friends, she found no joy in it. The laughter and chatter of the bar felt hollow, a stark contrast to the quiet, sterile environment of the hospital room where she spent most of her time. “I feel like I’m living in two different worlds,” she wrote. “One where I’m supposed to be a normal student in my twenties, and another where my brother is fighting for his life. I don’t know how to be in both.”

In the hospital room, the walls were now adorned with hundreds of cards—messages of love and support from family, friends, teammates, and even complete strangers to me. The outpouring of kindness was overwhelming, a reminder that we were not alone in this fight. Each card was a small beacon of hope, a testament to the impact I had made on the lives of others. My family would read them aloud to me, hoping that somewhere deep inside, I could hear their words, feel their love.

Yet, despite the progress, the reality of my condition remained stark. I was still trapped in a coma, my body restless and uncomfortable. I constantly tried to get out of bed, my movements erratic and uncoordinated.

The nurses had to restrain me to prevent me from hurting myself, a necessary but heartbreaking measure. My family watched helplessly, torn between the hope that I was becoming more aware and the fear that I was still so far from being truly awake.

As the third week drew to a close, my family clung to the small victories—the moments of eye contact, the occasional word, the attempts to comb my hair. They were signs that I was still there, still fighting.

But the road ahead was long, and the uncertainty of what lay ahead weighed heavily on all of them. They had learned to live with a new normal, but it was a normal filled with fear, hope, and the unrelenting desire to see me wake up.

This week was a testament to the resilience of the human spirit, the power of love, and the strength of family. For anyone walking a similar path, know that even in the darkest moments, there are glimmers of light.

Recovery is not a straight line, but every small step forward is a victory. My story, and the story of my family, is one of hope, perseverance, and the unbreakable bonds that hold us together, even in the face of unimaginable challenges.

Awakening Begins: Hopes & Fears: Day 22 - 28.

A Body in Motion, A Mind in Question.

The fourth week of my coma was a time of paradox, a phase in which the boundary between consciousness and intelligence began to become too reliable.

To the casual observer, it may have seemed that I too had emerged from the depths of the coma. My eyes were open and seemingly observing the world around me. But despite this outward sign of alertness, my neurological state remained unchanged, trapped in the limbo of unconsciousness.

My family, who had been watching my bedside constantly, were both hopeful and uncertain about what they saw. When they were present, my gaze often seemed to be directed at them, I recognized their presence. But beyond this fleeting acknowledgment, I gave no clear indication that I knew who they were or where I was.

My states fluctuated wildly between moments of serene silence and periods of intense restlessness. I lay quietly for half an hour, but was overcome by discomfort and agitation in the next half hour.

These unexpected changes in my behavior were especially pronounced during computed tomography (CT) scans, which made it almost impossible to take a real scan of my brain since optimal scan quality is determined by my body and head being at peace during the scan.

Amidst this bodily confusion, there were glimmers of hope that I was beginning to awake from coma. Slowly, I began to incorporate movement of my right side as well. The paralyzed right side seemed to take on new life, at slow pace, offering a glimmer of hope for future recovery.

One incident in particular stood out in my sister Nicole’s diary entries. As she documented the events of the day, I vigorously reached out my hand and withdrew her diary (from which I am documenting these stories) from her hands and installed it against my head. I held it there and even turned the pages as I read. My father, who witnessed this moment, saw my eyes moving from left to right, actively scanning the words as I did so. It was fleeting, mysterious behavior, but it spoke of the possibility that something was awakening in my sleeping brain.

The stadium of awakening was approaching and my focus was becoming increasingly directorial focused. I began to execute automic responses. When I sneezed, I automatically brought my hand to my mouth, a reflex that spoke of a growing awareness of myself and my surroundings.

However, these signs of coming out were accompanied by a deep sense of finality. My family wondered if it was really an awaking of my coma or if these were just fleeting glimpses of consciousness. It was loud and clear that the coma affected me physically, and so the biggest question that came up this time was: ‘‘Did the coma changed my personality?’’

The fear of the unknown hung over them, eclipsing the joy of each small step forward. The long, mysterious road to recovery still lay ahead, full of uncertainties, and they complicated the road to recovery, the challenges that awaited them.

Despite their worries, they found me supporting them, while their love and dedication remained unwavering. They were by my side every step of the way, celebrating every victory and marrying every failure.

This fourth week of coma was a testament to the resilience of the human spirit, the power of hope and the enduring power of love. It reminded us that even in the darkest of times, a glimmer of light can break through the darkness and lead us to recovery and healing.

My Mind's First Week Battle After Coma - in the Rehab Center.

Emerging from the Void: A Descent Into, and Ascent From, Disorientation.

"Officially declared awake," the neurologist's words echoed, cold and clinical, yet they meant nothing to me. My brain, a shattered mirror, reflected only distorted fragments of reality. I was supposed to be back in real life, but I wasn't. Reflecting years over it I remember those days barely, not directly after my coma, not now I was trapped in a liminal space, a twilight zone where the familiar was alien, and the self was a stranger.

The doctors called it "emerging from a coma", but it felt personally more like a descent into madness. A nightmare, yes, but one where the boundaries between sleep and waking blurred, where reality itself was malleable and terrifying. I wanted to scream, to tear myself apart, to do anything to escape the suffocating horror of this new existence. If there had been a knife, a rope, anything, I would have used it. Luckely, I was stuck to my bed that forbid me from doing such. From personal experience I can say that these moments waking out of the coma, or as it is professionally being called the Post-Traumatic Amnesia, are extremely difficult times for TBI survivors themselves and dangerous if not accompanied closely by physicians. While state of the art knowledge still proposes that absolute rest is needed during those periods, I would argue for a deep exploration (research) here. More in the link!

Awake by outsiders, but not for me. I had a desperate, primal urge to shock myself back into the life I knew, the life that was now a distant, unreachable memory. I didn't recognize this place, this body, these people who called themselves my family were foreigners to me. They were shadows, echoes, familiar yet utterly strange.

The people around my bed spoke to me, explained the accident, but their words were like whispers in a hurricane, meaningless and lost. I could see their faces, etched with worry and exhaustion, but their emotions were as incomprehensible as their words. I was a puppet, a hollow shell, and they were trying to pull the strings, but the connections were broken.

Then, one day, my mother cried with tears. Not a quiet, tearful moment, but a raw, heart-wrenching sob that shook the room. "Johan," she choked out, "it's difficult for us too." That single, vulnerable admission, that raw human emotion, pierced the fog surrounding my mind. For the first time appearing out from the coma, I felt something, a flicker of recognition, a spark of empathy. It was a fragile connection, a thin thread tethering me to the world, but it was there. But, that connection was short lived. The fog returned, and I was adrift once more, lost in the labyrinth of my own mind.

By being declared awake I was moved from the sterile, white walls of the hospital to the rehab center, in a Dutch town called Beesterszwaag. The ambulance ride, unlike the frantic, life-saving previous journey after the accident, was now a slow, deliberate journey into the unknown.

During that ambulance ride, the nurse accompanying me in the ride asked me what I wanted to become when I was older? ‘‘I wanted to be a police officer’’ was my response. I remember it being asked, and I remember my answer.

Although I was fifteen, I wouldnt give you this answer in the two years leading up to the accident. The accident mentally sent me back to primary school where this answer was prevalent.

Rehab center, Beesterszwaag, the Netherlands.

Beesterszwaag, the rehab center. My new home, a place of broken bodies and shattered minds. They gave me a private room, a small, living space that was to be my world for an indefinite period. Time had lost its meaning, stretching and contracting in unpredictable ways.

The rehab center was a microcosm of human fragility. Children, teenagers, adults—all victims of accidents, illnesses, fates as cruel and arbitrary as mine. I remember certain scenes vividly while the majority of it in the first weeks remain blurred.

In that first week at the lunch moments, a chaotic scene of wheelchairs and feeding tubes, of laughter and tears, of resilience and despair. I saw peers at the beginning of their recovery: I saw a 15-year-old being spoon-fed during lunch loosing mucus constantly because he was unable to secure it in his mouth. I saw a six-year-old, his limbs missing, his face scarred by fire wounds, yet his spirit and personality unbroken.

I think I remember it because it was so out of the ordinary, though it was my new home and my new normal through which there was no other way than to cope with it. I saw peers more advanced in their recovery: a talented young football player, recovered from his shattered knee, soon to be released from the rehab center.

There is no room for shame here, no judgment, each with their own story and a shared understanding of The Road to Recovery.

My hair, grown long and unruly during my coma, hung over my eyes, a constant reminder of the time I had lost. A hairdresser came, her touch gentle, her eyes filled with a quiet compassion. As she cut away the tangled mess, It was a small act of normalcy, a tiny step towards reclaiming a sense of self, but it was a step nonetheless.

My family saw a person that was still miles away from the old person who I was. I was nowhere near understanding where I was, what happened to me and what I was in need of doing towards the recovery all professionals predicted.

Even though they immediately started every possible treatment to help me get better as soon as I arrived at the rehab center, the first week is mostly a blank space in my memory. It's like trying to remember a faded dream, where bits of reality mix with strange, unreal feelings.

I have faint memories of hands, strong but gentle, moving my arms and legs through painful exercises, each movement reminding me how much my body had changed. I can barely hear the voices of the speech therapists, their words like distant echoes, trying to put back together the broken pieces of my ability to talk. And the tiring, constant physical therapy, forcing me to relearn simple movements, as if I was a baby trying to figure out a world that felt completely foreign.

Even though these sessions are mostly lost in the fog of my recovering mind, they were the quiet, unseen battleground where my fight to come back began, showing the unwavering dedication of those who refused to let me stay lost in the maze of my own mind.

Still to come and to be worked on, stick with me for a little bit ;):

‘‘My second week battle in the rehab center’’

‘‘My time in the rehab center’’

‘‘My road away from rehab to the University: being a graduated Master student’’

‘‘Living and working with TBI on three different continents: real life experiences’’

Many more

Having suffered severe trauma myself, sources that helped me to become the best version of myself:

Follow my personal survivors story by clicking here, having suffered severe TBI and the remarkable life story that brought me to where I am today.

Follow the Brain Recovery & Maintenance Protocol by clicking here, which is regularly updated with practical tips for long term brain recovery/maintenance care.

Follow MedPulse on The Omega Tree as it provides unique perspectives from trauma survivors and their stories.

Found this valuable? If you're interested in staying on the pulse of the latest advancements in brain health and receiving more content like this, hit that follow button!

Follow & Refer us on one of our other socials:

Follow, Subscribe and Donate when you feel good about that! Much appreciated as it fuels more stories like these.

On Your Wellness!

Disclaimer

Everything written here is based on my own account, if not otherwise stated. I am not a physician, nor do I have a medical degree. I was patient with them and by following certain and consciously not following other advice I found my way to become the best version of myself. I am a TBI survivor and I am sharing my experiences. From my own perspective I know what works and what not. My own perspective is always well researched and I only use products and services that have worked for me. Having said that, TBI survivorship is dependent on the individual going through TBI and therefore each case is different. One size - Fits all solutions don't exist in this space.

No monthly recurring payouts but can you miss a coffee? Support my writing here >> just once >> https://buymeacoffee.com/theomegatree Thank you!